Being a mad unapologetic Beatles fan, I really feel I should make some effort on the 40th anniversary of the release of Sgt Pepper, to force it somewhere onto this forum! So here is part of a news item (it mentions Beethoven - so don't panic!):

Yes, it's been 40 years exactly since Sgt. Pepper, having labored the previous 20 years teaching his band to play, arranged for its debut in full psychedelic regalia.

A hundred years from now, musicologists say, Beatles songs will be so well known that every child will learn them as nursery rhymes, and most people won't know who wrote them. They will have become sufficiently entrenched in popular culture that it will seem as if they've always existed, like "Oh! Susanna," "This Land Is Your Land" and "Frère Jacques."

The timelessness of such melodies was brought home to me by Les Boréades, a Quebec group that has recorded Beatles music on baroque instruments. The instruments give the sense that you're hearing Bach or Vivaldi, and for moments it's possible to forget that you're listening to Beatles songs. We're so used to hearing Beatles songs that for many of us they no longer hold any surprises. But when they're stripped of their '60s production and the personal and social associations we have with them, you can hear the intricate and beautiful interplay of rhythm, harmony and melody.

On the bus recently the radio played "And I Love Her," and a Portuguese immigrant about my grandmother's age sang along with her eyes closed. How many people can hum even two bars of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony, or Mozart's 30th? I recently played 60 seconds of these to an audience of 700 -- including many professional musicians -- but not one person recognized them. Then I played a fraction of the opening "aah" of "Eleanor Rigby" and the single guitar chord that opens "A Hard Day's Night" -- and virtually everyone shouted the names.

To a neuroscientist, the longevity of the Beatles can be explained by the fact that their music created subtle and rewarding schematic violations of popular musical forms, causing a symphony of neural firings from the cerebellum to the prefrontal cortex, joined by a chorus of the limbic system and an ostinato from the brainstem. To a musician, each hearing showcases nuances not heard before, details of arrangement and intricacy that reveal themselves across hundreds or thousands of performances and listenings. The act we've known for all these years is still in style, guaranteed to raise a smile, one hopes for generations to come. I have to admit, it's getting better all the time.

Daniel J. Levitin, a former record producer, is a professor of psychology and music at McGill University in Montreal and the author of "This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession."

Yes, it's been 40 years exactly since Sgt. Pepper, having labored the previous 20 years teaching his band to play, arranged for its debut in full psychedelic regalia.

A hundred years from now, musicologists say, Beatles songs will be so well known that every child will learn them as nursery rhymes, and most people won't know who wrote them. They will have become sufficiently entrenched in popular culture that it will seem as if they've always existed, like "Oh! Susanna," "This Land Is Your Land" and "Frère Jacques."

The timelessness of such melodies was brought home to me by Les Boréades, a Quebec group that has recorded Beatles music on baroque instruments. The instruments give the sense that you're hearing Bach or Vivaldi, and for moments it's possible to forget that you're listening to Beatles songs. We're so used to hearing Beatles songs that for many of us they no longer hold any surprises. But when they're stripped of their '60s production and the personal and social associations we have with them, you can hear the intricate and beautiful interplay of rhythm, harmony and melody.

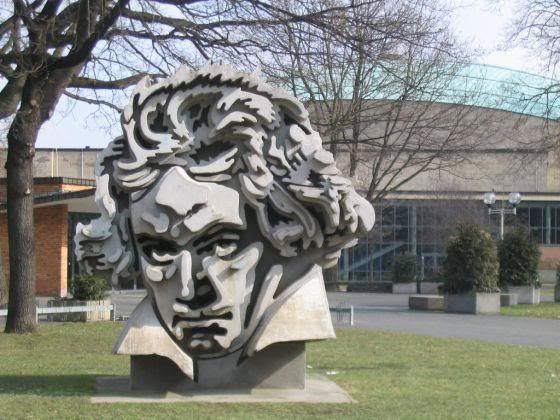

On the bus recently the radio played "And I Love Her," and a Portuguese immigrant about my grandmother's age sang along with her eyes closed. How many people can hum even two bars of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony, or Mozart's 30th? I recently played 60 seconds of these to an audience of 700 -- including many professional musicians -- but not one person recognized them. Then I played a fraction of the opening "aah" of "Eleanor Rigby" and the single guitar chord that opens "A Hard Day's Night" -- and virtually everyone shouted the names.

To a neuroscientist, the longevity of the Beatles can be explained by the fact that their music created subtle and rewarding schematic violations of popular musical forms, causing a symphony of neural firings from the cerebellum to the prefrontal cortex, joined by a chorus of the limbic system and an ostinato from the brainstem. To a musician, each hearing showcases nuances not heard before, details of arrangement and intricacy that reveal themselves across hundreds or thousands of performances and listenings. The act we've known for all these years is still in style, guaranteed to raise a smile, one hopes for generations to come. I have to admit, it's getting better all the time.

Daniel J. Levitin, a former record producer, is a professor of psychology and music at McGill University in Montreal and the author of "This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession."

)

)

Comment